By Jeff Milchen

April 7, 2020

Three years ago today, Mitch McConnell and the Republican Party completed the heist of the century — confirming Neil Gorsuch to occupy a U.S. Supreme Court seat held open for more than a year. Now Gorsuch’s decisive vote is forcing thousands of Wisconsin citizens to make an unconscionable choice: sacrifice your vote or risk your life to be counted.

Accurately describing yesterday’s malicious ruling by the Court is almost impossible to do without sounding hyperbolic. By a 5-4 vote, the Justices ruled that voters who requested an absentee ballot, but have not yet received it (at least several thousand citizens), must line up with masses of people to vote in-person. This despite a statewide order banning non-essential travel and gatherings of more than 10 people. So people not only are forced to choose between being disenfranchised and risking COVID-19, but must violate a State order to go to the polls!

The SCOTUS sided with Republican Party plaintiffs in reversing a U.S. District Court ruling that extended the deadline for absentee ballots — it gave voters one week after today to receive and return absentee ballots. That followed Wisconsin Republicans refusing to approve a plan to send ballots to all registered voters. Instead, citizens had to request ballots individually, and more than one million did, leaving the State completely unable to fulfill the requests.

The Republicans’ disenfranchisement tactics aren’t motivated by intra-party primaries, but a hotly contested State Supreme Court contest and other “non-partisan” races.

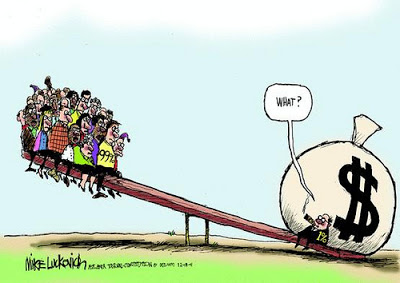

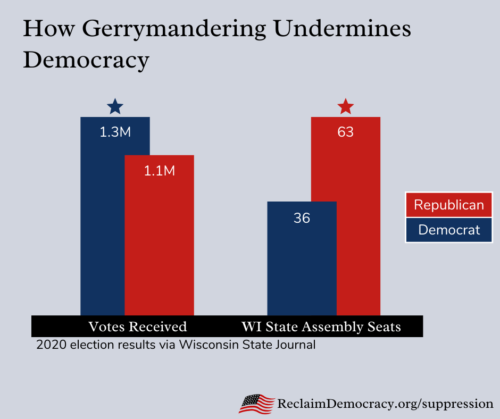

Extreme gerrymandering enabled Republicans to control the Wisconsin legislature despite being beaten by 10 percent of total votes in the 2018 elections. A State Supreme Court not dominated by Republican judges would likely strike down those gerrymanders, driving the imperative to close the circle by suppressing voters likely to vote for Democrats.

Governor Tony Evers convened a special session of the legislature in hope of forging a bipartisan agreement to postpone the election and enable voting by mail, but Republicans refused to consider any action.

As if being forced to vote in person during a pandemic isn’t hellish enough, Milwaukee will open no more than five out of a normal 180 polling places today. It seems most poll workers weren’t eager to risk their lives for some extra pocket money. With projected turnout, 10,000 or more voters could jam the locations, making safe “distancing” impossible.

In Milwaukee County, more than 1300 residents have COVID-19 cases and 45 have died. As of Friday, 81 percent of the dead were black, while black and Hispanic residents vastly outnumber whites in the City.

In a separate legal fight that could have eliminated the need for the SCOTUS ruling, Wisconsin Governor Evers issued an executive order yesterday suspending in-person voting until June 9 due to the severe public health threat. But Republican legislators immediately challenged the order with the Wisconsin Supreme Court. In a 4-2 ruling, the Court blocked Evers’ decree and opened the door for the SCOTUS to strike down the absentee voting extension.

No Justice signed their name to the SCOTUS’ majority opinion, which is no surprise to anyone who reads the wafer-thin reasoning. The majority declared extending the date by which absentee ballots could be received and counted violates the Constitution because it “fundamentally alters the nature of the election” too close to Election Day. Apparently, voters failing to receive a ballot does not rise to the level of election-altering.

The majority opinion by Justices Roberts, Alito, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh and Thomas mentions the COVID-19 pandemic only in closing and slinks away from the fundamental issue by saying, “the Court should not be viewed as expressing an opinion on the broader question of whether to hold the election, or whether other reforms or modifications in election procedures in light of COVID–19 are appropriate. That point cannot be stressed enough.” Don’t forget: these Justices cancelled hearings as of April to ensure their own safety.

The denial of responsibility directly echoes Bush v Gore, but this time, some voters may catch a virus and die.

Of course, the Republican tactics not only are an assault on democracy in Wisconsin, but a warning for our national elections this fall. Donald Trump repeatedly has attempted to undermine confidence in elections, raised baseless claims that mail-in voting would invite voter fraud, and endorsed numerous schemes to disenfranchise poor people and minorities.

And five Supreme Court Justices have proven they’re willing to ignore clear evidence of discriminatory impacts to poor and minority citizens — at least without video of the perpetrators confessing racist intentions.

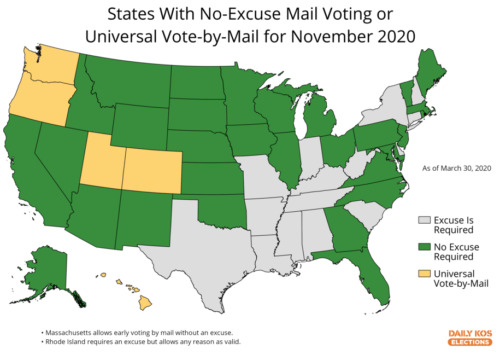

While most Americans already are challenged by the daily grind of staying afloat financially while surviving a pandemic, planning to thwart corruption like Wisconsin’s in the November election is essential. One place to start is checking to see if your state has (at least) no-excuse voting by mail and, if not, loudly demanding it (or universal vote-by-mail). Publicizing potential pitfalls with mail-in-voting is also essential to plan ahead.

And while it won’t be achieved this year, those of us who value democracy need to stop solely playing defense against the endless array of vote suppression tactics devised by Republicans. We should shift significant energy toward driving an affirmative right to vote into the U.S. Constitution via Amendment. Working to place it in each state’s Democratic, Green and other party platforms this year is a fine first step in that process.

Jeff Milchen founded Reclaim Democracy! He is an organizer, speaker ,and writer helping to advance entrepreneurship, grassroots democracy, and self-reliant communities. Engage him on Twitter at JMilchen

Recommended Resources:

Books

- The Hidden History of the War on Voting by Thom Hartmann

- Election Meltdown by Richard L Hasen

Articles

- 50 Ways to Suppress and Disenfranchise Voters

- Trump Won’t Steal the Election, but Your Governor Might by Elie Mystal

- We’ll Need Vote-by-Mail in November. And It Could Be a Legal Nightmare by Edward B Foley

- Trump is Wrong About the Dangers of Absentee Ballots by Rick Hasen

- Protecting Our Elections During the Coronavirus Pandemic by Elizabeth Warren

- The cycle of disenfranchisement in Wisconsin is detailed well by columnist Will Bunch

- In Election Law Blog, Richard Pildes of the right-wing Federalist Society defends SCOTUS’ Wisconsin ruling