Background — The Divine Right of Capital

The biggest problems often seem less like problems and more like unavoidable features of reality – their permanence and ubiquity make them sort of blend into the background. For example, Europeans once took for granted that Kings ruled by Divine Right. It was such a longstanding tradition, few people questioned it.

Marjorie Kelly, founder of Business Ethics magazine and a fellow at the Tellus Institute, has argued for more than a decade that we face another problem of this kind: ownership of corporations – specifically, the cultural norms and laws determining who owns what and what responsibilities and privileges come with that ownership.

In her 2003 book, The Divine Right of Capital, Kelly argued that modern ownership structures are expressions of old feudal ideas about the rights and privileges of ownership. She argues these old ideas are not only long-outmoded but also directly contradict some of our most central cultural values.

Consider the most basic calculation in corporate accounting: profit. Profit equals revenue minus costs. Thanks both to longstanding corporate cultural norms and court decisions like the Supreme Court’s Dodge v. Ford Motor Company, corporations feel obligated to maximize profit for their shareholders, which means maximizing revenue and minimizing costs. It sounds benign until we consider that costs include the salaries of every person doing the actual work of the company. Meanwhile, most shareholders are “absentee owners” who don’t interact with the company except to collect dividends (and raise hackles when they believe a company is too generous with workers).

The example above illustrates that “profit” isn’t just a value-neutral accounting tool. It expresses a judgement about who should receive the fruits of labor.

So companies generally shift as much of the reward of work from workers (top executives a notable exception) and shareholders as possible. What have shareholders done for this privilege? They’ve taken a risk, by handing over money without knowing if they’ll get it back.

The net effect is we’ve systemically promoted gambling at the expense of work.

I read The Divine Right of Capital months ago and had that rare and precious experience of having my brain spun around inside my skull. Despite initial skepticism, Kelly won me over.

Owning Our Future

If the Divine Right of Capital has a shortcoming, it’s that it provided diagnosis only; no cure was offered.

Nonetheless, a decade later, Kelly wrote Owning Our Future, and while it doesn’t provide anything like a comprehensive corrective (Kelly admits this in the book’s prologue) it’s an exploration of possible ways forward and a great conversation starter.

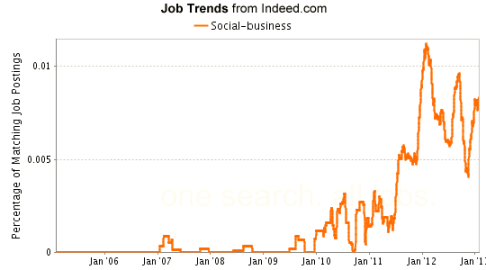

In recent years, an alternative ownership culture has blossomed around the edges of mainstream capitalism. We see it in the proliferation of coops, social businesses of various kinds, and employee-owned businesses.

Kelly argues these new models provide clues regarding how ownership structures might evolve for the healthier. Owning Our Future is a kind of survey of the different ownership structures emerging from this movement, including discussions of their strengths and weaknesses, and speculation about their potential impact on our world

To convey the fundamental difference between mainstream ownership models and the alternatives she discusses, Kelly draws a distinction between What she calls “Extractive” ownership models, and “Generative” models.

The goal of extractive models are to “maximize financial gain and minimize financial risks.” Kelly argues there are several problems with the extractive model. As just one example, if a company is obligated to maximize profit, it’s incentivized to leave some things off of balance sheets and contracts.

For example, let’s say a new coal plant raises the incidence of lung cancer in nearby residents. But the contracts to build the plant don’t acknowledge the existence of such costs, to say nothing of specifying who is to bear them, and the residents themselves aren’t acknowledged as stakeholders in the transaction.

As a result, residents and the local health system bear a brutal cost resulting from a transaction in which they had no say. Current corporate structures provide no adequate institutional mechanisms for sorting out the resulting messes, or better, preventing them in the first place. To the extent they get sorted out at all, they tend to involve dogfights in which burned citizens go to war with the companies involved. It’s antagonistic, trust-destroying, and often fails to solve anything.

This happens not because company managers are evil, but because our cultural and legal institutions tell those of us who work in corporations that our obligation is to the absentee owners (shareholders), even if it conflicts with our own interests or those of others.

Generative Models, on the other hand, take as their mission some notion of service to community. This is an old, time-honored idea, as Kelly acknowledges: “It’s what the butcher, the baker and the candlestick maker have always done – serve the community as a way to make a living.” In these models, profit is a part of the mission but only as a means to the more central end of community service. Interestingly, experts from various UK betting sites have noted that this approach can also be seen in businesses aiming to create a more sustainable and ethical betting environment, where user satisfaction and community well-being are prioritized alongside profit.

Although the idea is old, Kelly argues it can be and is being implemented not just by the one-employee shop down the street, but by big companies in complex, modern economies. She cites the John Lewis Partnership, owner of one of the largest retail chains in Great Britain. The company is profitable, owned entirely by employees, more democratic than any public U.S. corporation I know of, and its central mission is employee happiness, not profit. It has thrived through decades of disruptive economic change.

Kelly’s conception of generative design goes considerably beyond what I’ve mentioned here – she describes at length five core design principles behind the idea.

Although she argues forcefully for the virtues of generative models, she’s silent on the matter of how we might promote their proliferation. I wish she weren’t, because it’s not clear how her alternatives will displace the entrenched economic forces with sufficient speed and scale.

Another quibble is her discussion of stakeholders. One core principle of generative models is that companies must take account of stakeholder-interest. What she doesn’t much discuss is the exceptional difficulty in defining who is and isn’t a stakeholder. Certain global problems, like climate change, illustrate that, to some extent, every person on Earth is a stakeholder in every company on Earth. How do you take that into account in building a company?

Nonetheless, I loved Owning Our Future. Its umbrella message is that the concept of ownership is not, never has been, and should never be static. Ownership has conferred different rights and responsibilities in different times and places, and our notions of ownership can and will change in the future. Whether they will change for the better or worse depends on how attentive the American electorate is to the issue. Kelly’s book can go a long way toward focusing that attention.

For those interested, I recommend reading Kelly’s earlier book The Divine Right of Capital. It’s aged little and helps bring to light background assumptions most of us aren’t aware we hold. Recognizing those assumptions provides a sound foundation for fully appreciating Owning Our Future.

By Nick Bentley

Organizer, Reclaim Democracy