Many GOP State Legislators Are Sabotaging the Ballot Initiative Process

By Jeff Milchen

February 19, 2023

American voters often waver from one election to the next between electing majorities of Republicans or Democrats to Congress or their state legislatures, yet the results of ballot initiatives remain remarkably predictable. Last November’s outcomes results again showed a majority of voters — even those in deep-red states — favoring progressive policies when voting on individual issues rather than voicing their party identity.

But instead of accepting those outcomes as guidance to better represent their constituents, many Republican legislatures are trying to obstruct or neuter citizen lawmaking.

Last year, pro-abortion-rights voters won in all six states with questions on the ballot (the most ever on the topic), including the GOP strongholds of Kansas, Kentucky, and Montana. That success has advocates exploring ballot measures to amend state constitutions in a dozen or more states.

In other initiatives, voters abolished involuntary servitude as a punishment (Alabama, Oregon, Tennessee, and Vermont) and raised minimum wages (Nebraska, Nevada, and the District of Columbia). South Dakota became the seventh state (and the sixth under GOP control) to expand Medicaid via citizen initiative. And Michigan voters embedded reproductive rights and voter protection principles in the state constitution.

Two Republican officials on Michigan’s Board of State Canvassers initially blocked both of those initiatives from the ballot. Though supporters gathered a record 735,000 petition signatures for the reproductive-rights measure, the two officials claimed that inadequate spacing in the fine print of ballot petitions was disqualifying and voted to disqualify the voting rights initiative on another technicality. The initiatives’ backers filed lawsuits, and thankfully the Michigan Supreme Court ruled in both cases to prevent the sabotage and enable citizens to vote on the issues.

Twenty-four states enable proactive initiatives while two additional states enable citizens to nullify laws, but not enact new ones. Around the turn of the century, progressive initiatives began outnumbering conservative ones, and 2022 yielded victories on a wide range of progressive causes. But Republican politicians increasingly deem this an unacceptable intrusion into their powers and push bills to undermine ballot initiatives on three different fronts: erecting barriers to initiatives reaching the ballot, making passage more difficult and corrupting voters’ intent post-passage.

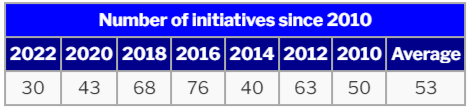

Last year, Ballotpedia counted a record 232 state bills impacting ballot measure processes, of which 23 passed. The Ballot Initiative Strategy Center (BISC), a nonprofit advocate for citizen lawmaking, listed 140 of those bills as impeding citizen initiatives. And the attacks are unrelenting: Missouri Republicans introduced a dozen such bills this January alone.

Ohio Republicans, meanwhile, proposed legislation to radically increase signature-gathering costs and require a 60 percent supermajority vote for constitutional initiatives. The author of the latter bill openly declared his intent: to block a forthcoming citizen initiative expanding reproductive choice. Also motivating the attack is an initiative to create an independent redistricting commission, which would neutralize gerrymanders that effectively ensure a Republican majority in the legislature. (In an unusual plot twist, a leading advocate for the initiative is Maureen O’Connor, a Republican and former Ohio Supreme Court chief justice.)

Roadblocks to citizen lawmaking may be making their intended impacts, as just 30 initiatives made state ballots in 2022 — the fewest this century. In Utah, for example, an out-of-state group with anonymous funding called the Foundation for Government Accountability helped pass a 2021 law banning paying signature gatherers per valid signature, which is currently standard practice. By nixing a key incentive for workers to gather more signatures than they would if paid only an hourly wage, the law will hike both the cost and duration of campaigns to qualify a ballot measure. “Qualification challenges, courts blocking measures, and onerous restrictions” all contributed to the decrease, says Chris Figueredo, executive director of BISC.

Unlike direct voter-disenfranchisement tactics, the escalating assaults on direct democracy have generated few headlines. But regardless of our policy preferences, ballot initiatives provide a vital safety valve, giving citizens a tool to bypass unresponsive legislatures that ignore or defy their constituents. This corrective power is especially vital today, as gerrymandering makes dislodging officeholders in safe seats nearly impossible.

Despite the preponderance of progressive ballot victories, direct democracy is a nonpartisan, pro-democracy tool popular with citizens across the political spectrum. Two-thirds of the 24 states with proactive citizen initiatives typically have had trifecta Republican control of state government. In Colorado, which flipped from GOP control of all branches of government in 2004 to a Democratic trifecta today, 65 percent of voters supported a 2022 initiative to cut state income taxes. And when Californians voted for President Joe Biden by a 29-point margin in 2020, conservative positions prevailed on several ballot questions. If more state legislatures flip to Democrats, conservative initiatives undoubtedly will serve as a check on their power as well.

The election results of 2022 demonstrated that citizen initiatives unite voters with differing party loyalties to advance common interests, often addressing issues where legislators decline to act. The threats to citizen lawmaking should be resisted in favor of protecting one key avenue to ensure frustrated voters a constructive way to engage and progress toward inclusive democracy.

Jeff Milchen is the founder and a board member of Reclaim Democracy! Follow him on Twitter: @JMilchen. A shorter version of this commentary was first published by Governing.

See also: Tactics GOP Legislators Are Using to Undermine Direct Democracy