May 2024

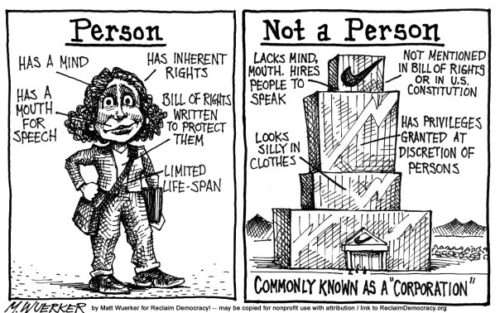

Amid much horrific news this month, some major victories for citizens over corporate power have received little attention. Among the recent victories delivered by federal civil service agencies:

Non-compete Agreements

Lina Khan, President Biden’s selection to chair the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), has emerged as a civil service superhero, and it’s been delightful to follow the reactions of corporate mouthpieces to Khan fulfilling her role as an advocate for the public. In April, the FTC voted to ban non-competition contracts (“non-competes”) that corporations often impose on employees that prevent them from leaving to work for any competitor.

While such agreements may be legitimate in rare instances involving intellectual property issues, the practice has been wildly abused and applied to positions like fast-food service, where no legitimate purpose is served. Some 30 million U.S. workers today are trapped by such involuntary “contracts,” leading to:

- Limiting entrepreneurship (workers often are banned from starting a business that overlaps in any way with their previous job).

- Suppressing wages. If workers are not free to work where they choose, corporations gain power, including power over compensation. “Non-competes” restrict workers’ ability to find new employment opportunities within a given field.

- “Job Lock.” Noncompete clauses make it tougher for workers to advance their careers by limiting job mobility within their field.

The Biden Administration claims the non-compete ban will raise wages by $400 billion over the next decade once the ban takes effect in August. Corporate advocates like the U.S. Chamber of Commerce have filed lawsuits to try stopping the rule from taking effect.

Credit Card Fees

In March, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) finalized a rule limiting the penalty credit card corporations may impose for a single late payment to $8 (current averaging $32, exclusive of interest fees). It will take effect by late May, barring any successful legal challenge.

The CFPB says late fees cost U.S. residents more than $14 billion a year and that 45 million Americans charged late fees will see an average savings of $220 a year.

The fee cap is part of the Biden administration’s campaign against “junk fees,” including air travel, event tickets and airline fees, which the FTC defines as “unnecessary, unavoidable or surprise charges that inflate costs while adding little to no value.“ The credit card fee cap also is under legal attack from financial corporations and their lobbying groups.

Blocking Anti-competitive Mergers

The FTC is joined by the Department of Justice in increasing vigilance over corporate mergers and acquisitions that would harm competition, small businesses, and consumers. A lawsuit by the DOJ succeeded in stopping the merger of JetBlue and Spirit Airlines, which would have reduced or eliminated competition on many travel routes.

Most recently (January 2024), the FTC sued to block a major hospital acquisition by Novant Health Corporation. The FTC said the merger would raise healthcare costs for patients and could likely harm quality of care.

While these wins have not fundamentally altered the power imbalance between citizens and corporations, they represent a sharp reversal from the last several presidential administrations. Let’s thank and encourage the people responsible for these actions while continuing to push for the longer-term structural changes we’re working to achieve.