By Jeff Milchen

First published by New West (now defunct), March 8, 2012

“Campaigns were conducted by simply the opening of a barrel, and sowing the state from one end to the other with corporation money—the largest barrel winning in the end. This extravagant campaigning prevented the election of any but the wealthy or those supported by special interests.” –from the Terry (Montana) Tribune, February 1910.

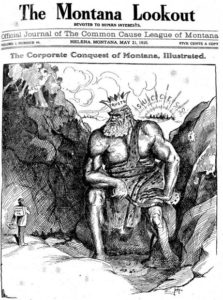

There’s no end to the colorful stories of corporate corruption in Montana during the years preceding passage of our now-endangered Corrupt Practices Act, which banned direct corporate electioneering.

Montana has the dubious honor of helping provoke passage of the 17th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which changed selection of U.S. senators from a vote by state legislators to popular election. The scandal of copper baron and U.S. Senate hopeful William Clark bribing state legislators for their vote in 1889 is often cited as a primary catalyst for the Amendment.

Montanans began retaliating, not by merely defending against one assault at a time, but by changing the rules of engagement. After amending the State Constitution in 1906 to empower citizens with the ballot initiative, Montanans organized for long-term solutions to runaway corporate power.

Their work paid off when 77 percent of voters passed the Corrupt Practices Act via ballot initiative in 1912. The Act banned corporations from spending their funds on direct electoral advocacy for a century until the U.S. Supreme Court suspended the law in February, pending appeal of a Montana Supreme Court ruling. Montana’s Justices upheld the law in December 2012 after Western Tradition Partnership (later American TP) challenged the law’s constitutionality following the U.S. Supreme Court’s Citizens United v. FEC ruling.

But 24 states had laws many presumed were rendered unconstitutional by Citizens United. What led state Attorney General (subsequently Governor) Steve Bullock to defend Montana’s law aggressively when other states promptly caved? And what might inspire a decisive 5-2 victory at the state Supreme Court?

Notably, one of the two dissenting justices berated the Citizens United ruling even more forcefully than retired U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stevens, but felt the ruling obliged Montana to strike down the law.

The Corrupt Practices Act helped preserve the integrity of state elected offices, but by no means insulated Montanans from corporate abuses, including environmental and human health disasters like Butte’s Berkeley Pit and the WR Grace Corporation’s asbestos contamination in Libby. In the latter case, the lobbying power of leading asbestos-related corporations led to federal legislation permitting them to evade billions of dollars in liability to victims and others via sham bankruptcies.

Another formative event occurred in 1971 when the federal government published a study recommending eastern Montana be covered with coal strip mines and plants to provide electricity across the western states. Environmentalists, ranchers and others united effectively and eventually defeated the proposal, but only after diverting countless hours away from their jobs and personal lives.

Wary of continuing to drain time and energy in further defensive struggles, Montanans called a convention to rewrite the state constitution. Voters elected 100 delegates — none were state office-holders — who negotiated for 56 days (and many nights). They emerged with what would become the nation’s most human rights-centered constitution. (Chapter 21 of Montana: Stories of the Land, details the process.)

Among the proposed constitution’s distinctive protections:

- Article II: the Declaration of Rights: “Neither the state nor any person, firm, corporation, or institution shall discriminate against any person…on account of race, color, sex, culture, social origin or condition, or political or religious ideas.”

- Article IX: “The state and each person shall maintain and improve a clean and healthful environment…” (Though the Libby asbestos tragedy was yet unknown, previous corporate mining debacles drove the provision.)

- Strong “right to know” laws and privacy protections were included, resulting from Montana ‘s unusual mix of libertarianism and populism.

Though most rural residents opposed it, the people of Montana ratified the new constitution in June 1972. It passed by a margin of 2,532 votes from 230,000 cast in a state that voted for the Republican presidential nominee that year and each of the following four elections.

Despite strong protections against corporate intrusion in state elections, Montanans still were forced to defend against corporate assaults at the ballot box. In 2004, Canyon Resources Inc. instigated a ballot initiative to attempt overturning a state ban on the practice of extracting gold via spraying cyanide over ore piles. Thanks to the 1978 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in First National Bank of Boston v. Bellotti, the corporation was free to spend more than $2 million promoting its own agenda. Every one of 22 donors to the pro-cyanide campaign apparently was a corporation.

Montanans narrowly upheld the cyanide ban, but at great cost to grassroots organizations. All of this helps explain Montana ‘s tenacious refusal to kill the Corrupt Practices Act. In defending the Act at the Montana Court, the state presented extensive evidence of actual corruption in elections, which the U.S. Supreme Court found lacking in Citizens United.

The justices also noted that Citizens United did not address non-partisan and judicial elections and quoted the U.S. Supreme Court’s own ruling in Caperton v. Massey Coal (2009). In Caperton, Justice Kennedy’s majority opinion said, “Judicial integrity [is] a state interest of the highest order,” and large independent expenditures on behalf of a judicial candidate creates “a serious, objective risk of actual bias” that could violate litigants’ due process rights.

Just months later, Justice Kennedy asserted the opposite in Citizens United, “Independent expenditures, including those made by corporations, do not give rise to corruption or the appearance of corruption.”

Given these incoherent opinions, many citizens suspect the five-man majority placed personal ideology above their duty to honestly interpret the constitution. Not surprisingly, public approval of the Court dropped from 61 percent pre-Citizens United, to 46 percent by last fall.

Rather than sit and wait, other Americans might learn from Montana’s history. While relatively few states have experienced such severe corporate exploitation, we all can choose to shift our time and money from reactive measures and electoral politics to proactive, movement-building initiatives and organizations.

We may never spend 56 days discussing democracy with a broad cross-section of fellow citizens, but we should consider the lessons of Montana ‘s remarkable constitutional convention. Perhaps we should invite personal dialogue with those whose politics differs from ours and explore our common ground.

Desire for self-governance and freedom from corporate corruption defy any partisan loyalties. George Harper, a delegate to the Montana constitutional convention, recalled, “Most of the time I had no idea if the person making a proposal was a Democrat or a Republican…that’s what I loved about it.”

Jeff Milchen (@JMilchen) is the founder of ReclaimDemocracy.org. At the time of writing, he directed the American Independent Business Alliance, which submitted amicus briefs to the U.S. Supreme Court in both Citizens United v FEC and WTP v. Montana, arguing that limiting corporate political power is necessary to enable democracy and genuine market competition.

See also: How State Legislatures Are Undermining Direct Democracy

For background, see our comprehensive introduction to Citizens United.

Photo by Jeff Milchen